Ahoy everyone!

Whilst I am extremely partial to writing1, I am by trade an Engineer. I have long had suspicions that my training in problem solving was influencing my worldbuilding, and when I stopped to think about it, I think that I might be onto something!

So, let’s talk about an Engineering problem solving method, and how it can work wonders for Worldbuilding in fiction - both Dungeons and Dragons, and the wider world of storytelling!

5-Why Analysis

The 5-why analysis is a misnamed system, but it’s vaguely catchy and significantly shorter than “keep asking why until you can’t any more”, so that’s what it’s called.

5-Why Analysis is an excercise in driving to the root cause - this being the fundamental, base-level thing that causes the problem or effect. This can lead to multiple results, and can branch out when needed - this is less beneficial for solving engineering problems, but it is wildly useful for making logical, coherent and causal worlds for your favourite fictional endeavours.

Let’s take an example of the Dwarves in Arenstar.

The final statement is where you begin the process - because the process works backwards from here. In Engineering, this is called the Problem Statement, but in worldbuilding, I think of it as the final result - the thing in my world which needs to be explained.

For my Dwarves, it is this:

The Dwarves of Arenstar have a greater affinity with wood than they do with stone, because they have learnt to work with it instead of mining.

A good and simple bit of worldbuilding, and you could be excused for stopping there - these are wood dwarves, they prefer choppy-choppy-tree to diggy-diggy-hole, and that’s that. But I don’t stop here - I ask a specific “Why”. It’s important to be specific, because just saying “why?” sometimes doesn’t help, or sends you in the wrong direction. Asking “Why” to this might result in the answer “Because they need to build out of something, and without stone as an option, they chose wood”, which doesn’t help answer the important question:

Question: Why did the Dwarves stop digging?

There it is - the question most of you have asked when seeing that statement about the Dwarves, and one which might have gone unanswered if I, the author, had not asked it of myself. The world is about to gain a layer of depth, my friends, beyond the vaguely interesting factoid about Dwarves.

The Dwarves stopped digging because…

That’s how we start. Write the story, but don’t go into metaphors and linguistics - write it like it’s a 4-point exam question and you know there’s no points for artistic writing.

The Dwarves stopped digging because they were driven out of their homeland by the Giants, and there’s nothing worth digging up outside of the mountains.

I’ve just added a war, a region, a fact about the world, and an explanation. The tree grows shoots, and now we can explore the branches:

Why isn’t it worth digging outside of the mountains?

Why did the Giants drive the dwarves from their homeland?

These are, to my mind, the burning questions. One is political, and the other is geographical.

Those familiar with the world of Dungeons and Dragons will know of the Underdark. This is a hollow world, and beneath the surface, the endless tunnels and caverns link and relink, forming an entire world of darkness, underneath the surface world. This is the underdark.

Thus, I can weave an explanation, and expand my world:

The Dwarves do not dig caverns outside of the mountains for two reasons. Firstly, because they do not wish to lay down roots - they will reclaim their homeland, one day, and no tunnels dug between now and then could compare. Second, the Mountains formed a natural barrier between the surface and the underdark, and without this barrier, it is dangerous to attempt anything more ambitious than a narrow mine in a hillside.

Through this, I have created the splendour of the lost dwarven kingdom, described the topography of the world, Explained the pride and the cauthion of the Dwarves, and added a future conflict - the reclamation of their homeland. Now for the second question. I have decided that this was not a personal attack, but a logistical convenience:

The Giants drove the dwarves from their homeland as the first part of a bid to conquer the world. The homeland of the Dwarves was on the northern border of Arenstar, and as such, was simply the first step in the Frost Giant’s attempt on the world.

Lovely - we have a BBEG forming already here, and more questions to answer!

We’re 3 layers of “Why” in, and that simple statement about the Dwarves liking to work with wood is building an entire world around it, with political conflicts and all sorts. Let’s dig deeper!

Why did the Giants stop their attack if they succeeded in taking the Dwarven homeland?

Why are the Dwarves spending time learning woodwork when they wish to reclaim their homeland?

These would be, to my mind, the main questions here. Everything almost makes sense, but the problem is, the Dwarves must have been out of their home for a while to be picking up a natural affinity for woodwork instead of stonework, and the Giants won, so why isn’t the world overrun by giants - or the giants beaten back, and the dwarves allowed to go home?

I can do this tidily, methinks!

The Dwarves have had time to learn, and the giants have stopped their campaign, because the dwarves mounted an immediate retaliation, to reclaim their home. They assaulted their own lands, but they were repelled. In their actions, however, they managed to cripple the Giants, taking away some source of power, and the leader of the Giants opted to stop the campaign until the power source was returned.

Now we have an uneasy status-quo2, which is good for the entry point of a game. For D&D, I like to make it so that the world is finely balanced, and then I unleash my party of chaos-munchkins and hope for the best. “An boject will remain at a constant velocity or at rest unless acted upon by an external force”, and I aim to make the party that force - they are the main characters in the story, and if they don’t get involved, nothing much changes.

Now we have some more questions which will help make sense of it:

Why is the Giant leader waiting?

How did the Dwarves do so much better at reclaiming than defending?

The answer to the first one is where the BBEG forms for the campaign:

The Giant Leader is waiting because he is not affected by the passing of time, so can wait as long as he sees fit.

Ooh, that’s a good one, and sinister too. I have a good plotline behind this now, but can’t reveal too much - the campaign is still going, after all!

As for the second question:

The Dwarves almost succeeded in their assault on their homeland because they recruited the help of the few remaining Dragons in the world.

How’s that for a twist? Dwarves and Dragons working together? talk about rejecting fantasy stereotypes…

So what did we get?

From that simple statement, that Dwarves are woodworkers in Arenstar, I have worked backwards and created:

Concepts for at least 3 sections of world (Giant homeland, dwarven homeland, the underdark) that I can flesh out.

An historical conflict, with a conclusion.

A sinister BBEG-candidate.

Dwarven attitudes in Arenstar (cautious, friendly to dragons, stubborn, and proud).

A mysterious something which the BBEG candidate wants.

A world which is not currently moving - that the protagonists can tip with but the slightest actions.

All of which are immensely useful for making a world, and which all make sense, thanks to the 5-Why Analysis!

Added Complexity

the 5-Why Analysis is a strong tool for simple problems with few potential causes. The Dwarves are a good example - pragmatic and grudge-filled, their actions are fairly predictable, with cause and effect plainly on the surface.

When it comes to things more political, I will be trying a different tool - and this is something I’m actively working on for the campaign, so it’ll have to wait until the party have started navigating it before I publish it!

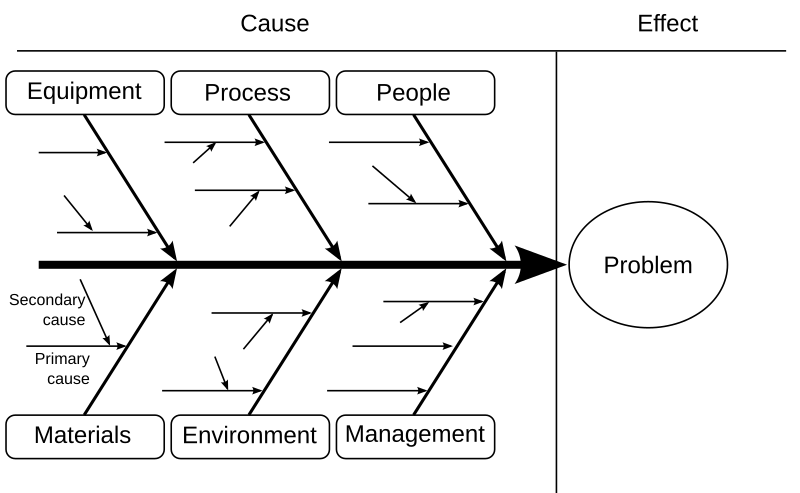

The tool I intend to use is a variation of the Fishbone Diagram.

Fishbone diagrams resemble cartoon fishbones3, and they show how multiple influencing factors can result in an outcome. Each reason then sprouts it’s own fishbone diagram as to why, allowing you to drive downwards to root cause.

I’m not trying to find the root cause for a real problem - I’m looking to make a political environment where everything makes sense, and the viewpoints of everyone involved are founded in cause & effect, allowing the players of the game to navigate the cause to elicit the effect. This is perhaps less necessary in fiction writing, where you have control of the protagonist4, but in D&D, I need to know what the party can affect and what it might do. They’ll still surprise me, and none of this will be used, but I’ll make it anyway - them using it might be the surprise!

Once the next few sessions are past, I will expand on the Fishbone diagram to say what worked and what didn’t! for now, I recommend practicing the 5-Why Analysis on some of your world, and seeing what comes out of the metaphorical woodwork5!

If you enjoy reading my articles, and want to see more, then hit subscribe!

If you’ve got ideas for monsters or articles, then let me know in the comments!

And if you’ve something for me to review for Third-Party Thursdays, then definitely message me!

And if you like what you’re reading and want to help me afford professional artists to illustrate my work for publication (and fight against the terror of AI Artwork), consider buying me a Ko-Fi!

Finally, if you love TTRPG content, then head over to DrivethruRPG - it’s packed with thrid party D&D content, unique TTRPGs, Pathfinder supplements - pretty much anything you could want for TTRPGs!

Spelt: “Wallfing on on the internet”.

You can also creat an uneasy status-quo by following the 70’s rock band around whilst dressed as the grim reaper, always appearing in the distance, always staring. Due to a restraining order, I cannot.

If you need to see this, simply swallow a whole fish and then immediately regurgitate the intact, bare skeleton, like a cat.

Mine are more akin to dropping beyblades into a game of hungry, hungry hippos.

If things start coming out of the literal woodwork whilst you are practicing this, you may need to branch out from eldritch horror as a genre until you fumigate the house.